We’ve written before about Buffalo’s innovative architectural history–it’s one of our favorite things about the city.

To celebrate one of the city’s most famous landmarks, we wanted to take a deep dive into the history of the Richardson Olmsted Campus.

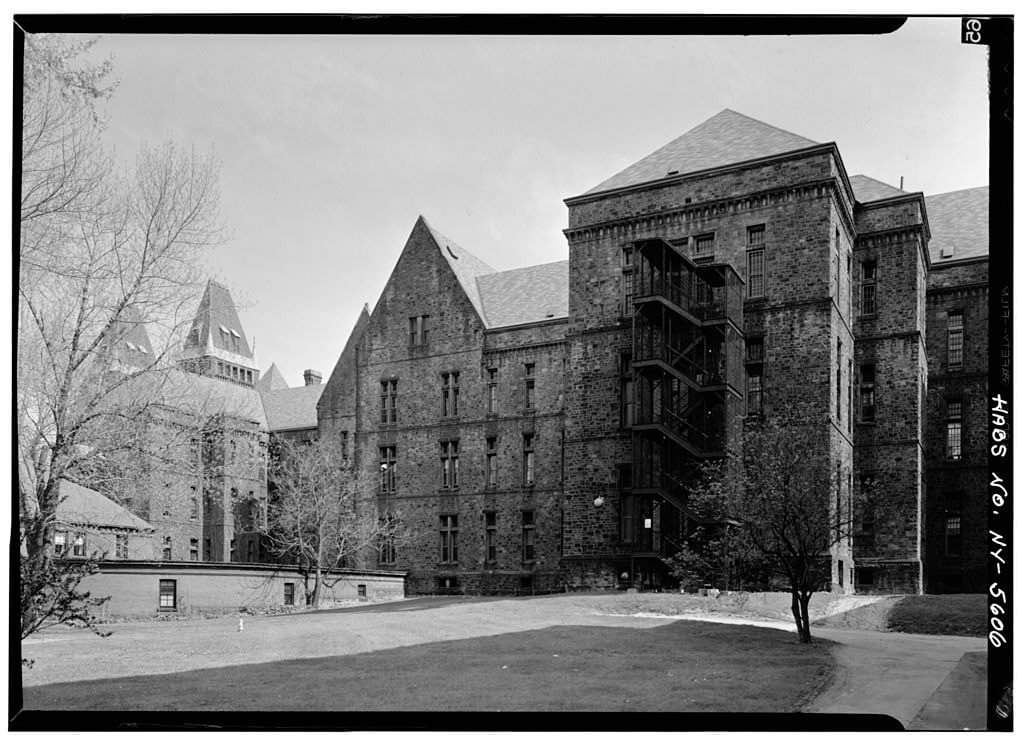

The Richardson Olmsted Campus is a 42-acre site located on Forest Ave. featuring some of Buffalo’s most iconic buildings, historic architecture and gorgeous grounds.

The complex opened in 1880 as the Buffalo State Asylum and provided care for nearly a century until its last patients moved out in 1974. It was listed on the National Register for Historic Places in 1973, and the site was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

Who Designed the Richardson Complex

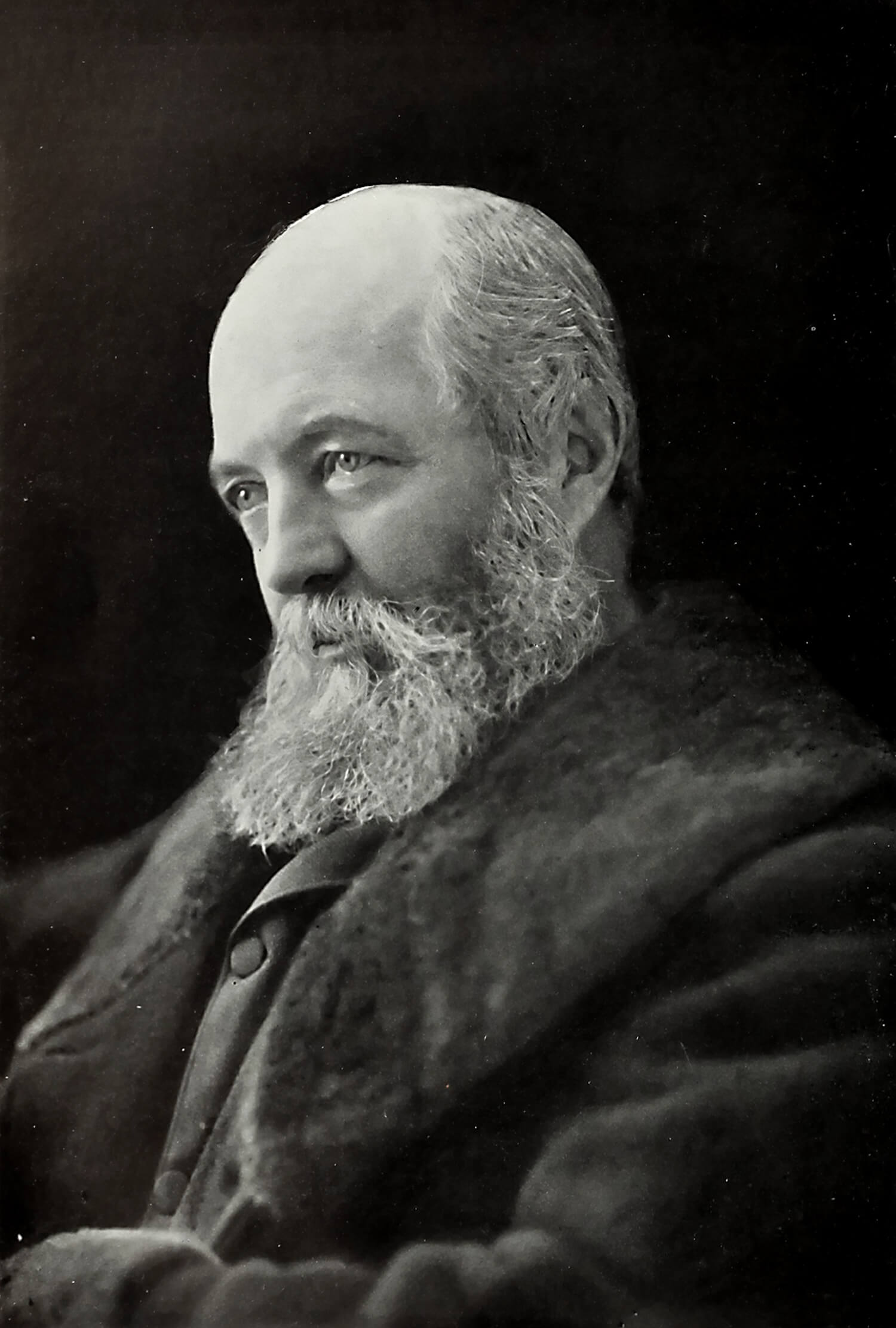

The Richardson Complex was designed by and named after Henry Hobson Richardson, who, along with Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, is considered one of “the recognized trinity of American architecture.” He is considered the father of the Richardsonian Romanesque architectural style.

But the buildings were not the only parts of the project designed by a famous architectural figure. Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of Manhattan’s Central Park along with Buffalo’s expansive system of parks and parkways, designed the gorgeous grounds and gardens surrounding the campus along with architect and landscape engineer Calvert Vaux.

In addition to these top-notch architects, Thomas Story Kirkbride was involved in the design of the complex. Kilbride was a founder of the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane, a precursor to the American Psychiatric Association. His involvement was crucial for a complex that was intended to provide innovative and compassionate care to mentally ill patients.

The Beginnings of the Complex

As we’ve written about before, the city of Buffalo experienced massive growth in the 1800s due to the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. The population doubled through the mid 19th century, which, along with its vast amounts of land and proximity to water, made Buffalo the ideal candidate for a new state mental hospital, according to the campus’s website.

In 1869, the New York State legislature authorized the creation of a new mental asylum for Western New York, and Buffalo was chosen after the city guaranteed the hospital a free “perpetual supply of pure Niagara water.” Buffalo’s status as a transportation hub, along with its nearby medical college, were also key factors in the decision to open the hospital there.

At the time, Frederick Law Olmsted had recently completed his design of the Buffalo Park system, and he was asked to design the new campus for what was to be called the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane. The project managers asked Olmsted for a recommendation for an architect, and he recommended his friend and next-door neighbor, H.H. Richardson. The state hired Richardson despite his minimal prior experience, and the project would become the largest of his career.

Richardson worked with Thomas Story Kirkbride to design the complex in a way that worked with the “Kirkbride Plan” of treatment, which focused on a calm, airy environment for people with mental illness. Kirkbride’s system was known as “moral management,” and he believed that a peaceful environment could help treat and potentially cure patients’ issues.

Opening & Construction

Hospital construction began in 1871, and the complex was opened in 1880, when half of the buildings were completed. The eastern wing of the hospital featured five large wing buildings, which housed up to 300 patients. The huge central Administration Building featured two towers, which overlooked the community below.

Richardson died in 1886, however, before the rest of the complex could be funded and completed. Other architects, including Green & Wicks and W.W. Carlin, continued to design the remaining buildings, using inspiration from Richardson’s plans.

In 1889, construction on the western wing began with its own five connected wing buildings, completing Richardson’s original intended symmetrical design. The full wingspan of the hospital was completed in 1896.

Expansion & Evolution

In the early 1900s, the standard of treatment for mental illness evolved from the Kirkbride Plan of “moral management” to Cottage Style, a philosophy focused on small groups of patients living in cottages rather than large hospitals. There was a belief that this could help create a better sense of community and help influence patient behavior by creating a “home-like” feeling.

From 1900 to 1945, the hospital had several expansions to facilitate this new philosophy of treatment, including building a new chapel, new residences for the staff, workshop buildings, occupational therapy centers, and cottage-like pavilions for patients with tuberculosis.

Nearly 100 acres of the site’s footprint was also dedicated to farmland, which provided food for the hospital and served as a place for patients to work as part of their therapy. It was eventually sold to Buffalo State, however, and became a part of what is now the university’s campus.

Patient population peaked in 1950 when the hospital housed 2,766 patients. The population began to decline over the next decade, however, due to improvements in medication and treatment and a shift toward community-focused care as opposed to large state hospitals.

Modernization & Closure

In response to a call for more modern buildings, new construction continued into the 1960s, and some historic buildings were demolished.

In 1965, the new eight-story Reception and Intensive Treatment Building (named the Strozzi building) was opened to the east of the historic buildings, providing 544 new patient beds.

The hospital also made the decision to demolish the three eastern wing buildings of the original Richardson design and replace them with a new, one-story rehabilitation center (named the Butler Rehabilitation Center), which was completed in 1970. This decision dramatically changed the historic configuration Richardson had conceived nearly a century before.

As patient population continued to decrease in the 1970s and it became increasingly difficult to maintain the large historic buildings, the decision was made to move all remaining patients into the modern Strozzi Building. The last patients moved out of the historic wing buildings in 1974 and they were vacated.

The historic nature of the buildings led to the site being placed on the National Register for Historic Places in 1973, and it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986.

First Revival

In the early 2000s, there were calls to rehabilitate the historic buildings, and $100 million in funding was secured in 2004.

The plan for the site was focused on finding new, economically sustainable and community-focused functions for the buildings.

As part of the plan, the historic buildings were stabilized and preserved, with workers reinforcing areas in danger of collapse, repairing roofing, installing new exterior lighting, sealing broken windows, and installing ventilation and security systems.

A key goal of the rehabilitation project was opening up the 42 acres of the campus to the public. As part of this plan, the South Lawn greenspace was completed in 2013. This greenspace was originally part of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s design for the hospital grounds but had been paved over in the twentieth century to make room for two large parking lots. In addition to the removal of the parking lots, the project included planting 125 new trees and environmentally-friendly rain gardens to help create a nature-focused space for community and recreation.

Redevelopment of the campus continued and in 2014 there was a massive project to transform the complex into a high-end hotel with 88 rooms and large conference and event spaces. This opened as Hotel Henry in 2017. As a result of the successful project, in 2018 the Richardson Olmsted Campus received the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation National Preservation Award, which recognizes and celebrates the “best of the best” in preservation projects across the country.

While they were successful for many years, the hotel and adjoining restaurant were greatly impacted by government-mandated restrictions and closures during the pandemic, which reduced/eliminated operating income, and both were forced to close.

Revitalization & Reopening

Fortunately, over the past few years, the non-profit Richardson Center Corporation was able to partner with Douglas Development to re-open the hotel and conference center and relaunch them as the Richardson Hotel. The development company will also help maintain and adaptively reuse the majority of vacant buildings on campus.

The Richardson Hotel opened earlier this year, and already visitors have been raving about the “gorgeous” design and “striking” architecture.

The hotel occupies three of the 13 buildings designed by Richardson. Meeting rooms and the ballroom are named for Richardson buildings, and the suites are named after Olmsted parks. One wing of rooms, once used as the female hospital quarters, is named “Hobson,” Richardson’s middle name, and the men’s quarters are named after Olmsted. According to general manager Karen Oleszak, the hotel has been full most Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays.

Besides the hotel, there are several new eateries at the complex. The Calvert Cafe and the Vaux Bar (named after architect Calvert Vaux) opened in April, and the Cucina restaurant opened in July.

In addition, following the community-created master plan, the Lipsey Architecture Center Buffalo has opened its first gallery on the campus to celebrate Western New York’s rich architectural heritage. The gallery can be found on the ground floor of the historic towers building and is free and open to the public. A project for a larger, more interactive gallery space is also in the works.

According to The Buffalo News, there is also a plan to develop nine of the 10 remaining buildings and turn them into more than 200 residential units. Environmental remediation is expected to be completed by the end of the year, with construction to soon follow.

Fair Housing Notice

Fair Housing Notice